There is growing interest in the use of local materials – including earth:

Nowadays, the understanding of our building culture and the application of local construction methods may seem like a distant and obsolete concept given the role of industrialization and globalization in the construction industry. We can now obtain almost any material from around the globe just by searching the internet for a distributor in our region. But this practice has important implications for our society, from the loss of architectural identity to environmental costs related to high CO₂ emissions associated with the processes of extraction, manufacturing, transportation, and disposal of these materials.

The increasing global need to reduce our carbon emissions and use materials in more efficient ways has led us to research and learn about the origin of our region’s resources, eventually leading to better understanding their applications within a circular economy approach. But why not look right under our feet? Soil is one of the most common materials on the planet, and when it is locally sourced, it does not generate considerable amounts of embodied CO₂. It seems that after industrialization, we have forgotten that building with earth was for many years a viable construction method for our ancestors in different parts of the world. We spoke with Nicolas Coeckelberghs, one of the four founders of BC Materials, a worker cooperative based in Brussels that has been working with earth, rediscovering its use, and sharing its knowledge on a global scale while working with a local conscience.

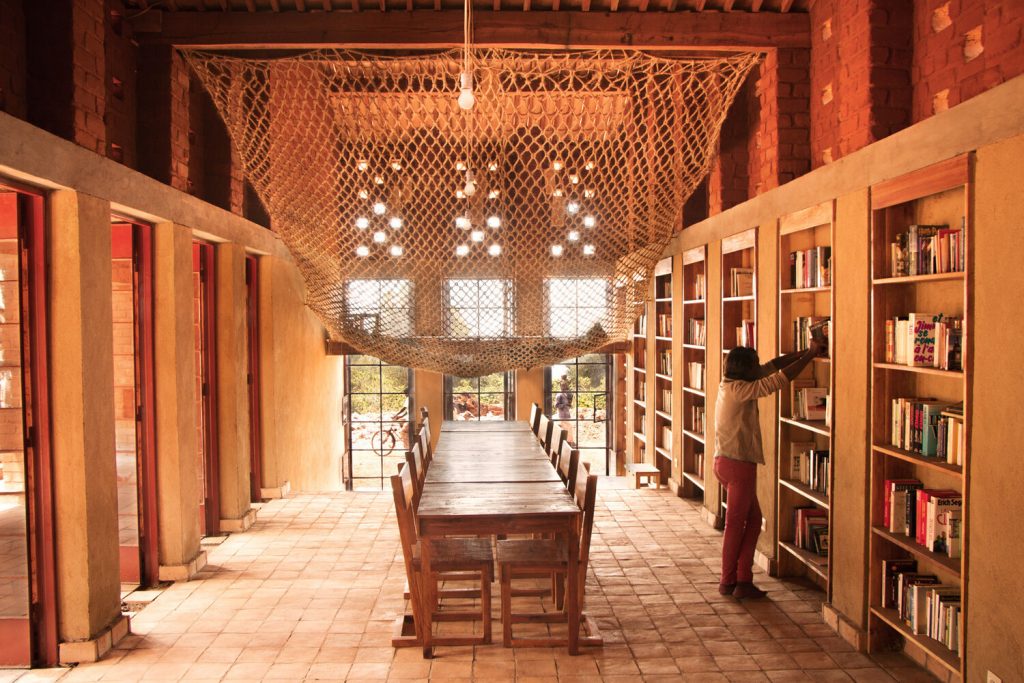

Using local materials has a clear ecological but also economic purpose. In countries where industrialization took place with reduced intensity, this practice makes sense given the high costs of industrialized materials such as concrete, cement, and steel, which usually have to come from abroad. An example is the Library of Muyinga project developed in the Eastern Africa region by BC Architects —a parallel practice to BC Materials— where a construction process involving both end-users and second-hand economies was conceived. The library was built with a participatory approach using locally sourced compressed earth blocks and local labor.

Building with Waste: Transforming Excavated Earth into Architecture | ArchDaily

Yes, we can build according to the local terrain, the local climate and the local resources: Build housing according to where we live! – Sidmouth Solarpunk

And that includes cob in damp Devon: Ottery builder claims ‘king of the cob’ title from Grand Design presenter after biggest ever build – Vision Group for Sidmouth and Building Cob Houses > talk in Lyme Regis – Vision Group for Sidmouth

Grand Design’s return to cob house that ‘broke up a family’ ‘best ever’ | Daily Mail Online and ‘The most requested Grand Designs revisit in history’: inside the extraordinary Lord of the Rings-style ‘cob castle’ home in Devon | Homes and Property | Evening Standard

Sounds natural! Vernacular architecture – and low energy – Vision Group for Sidmouth